The Bioinformatics CRO Podcast

Episode 51 with Adam Freund

On The Bioinformatics CRO Podcast, we sit down with scientists to discuss interesting topics across biomedical research and to explore what made them who they are today.

You can listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon, and Pandora.

Adam is founder of and CEO of Arda Therapeutics, a company using single-cell sequencing to characterize and target pathogenic cells to treat chronic diseases and aging.

Transcript of Episode 51: Adam Freund

Disclaimer: Transcripts may contain some errors.

Grant Belgard: [00:00:00] Welcome to the Bioinformatics CRO Podcast. I’m Grant Belgard and joining me today is Adam Freund, the founder and CEO at Arda Therapeutics. Welcome, Adam.

Adam Freund: [00:00:10] Thanks, Grant. I’m happy to be here.

Grant Belgard: [00:00:12] Yeah, we’re happy to have you. So what can you tell us about Arda?

Adam Freund: [00:00:16] Arda is a seed stage biotech startup. We are based in the Bay Area, and our mission is to find and eliminate pathogenic cells. And we do this in chronic diseases and ultimately in aging itself.

Grant Belgard: [00:00:30] How do you think about pathogenic cells? What in your mind makes a cell pathogenic?

Adam Freund: [00:00:36] It’s a great question. At a high level, cells are the functional units of life. And because of that, we also think that they’re the functional units of disease, which to put it another way is that when a tissue goes wrong, it’s because cells within that tissue have gone wrong. And in some cases, the cases that are particularly relevant to Arda, that means too much of a particular cell type. So think for example, myofibroblasts in fibrosis. They’re an important wound healing cell type, but in certain diseases they become overly abundant and then they don’t resolve or go away when they’re supposed to and so you get disease. And in cancer therapy, targeting and eliminating pathogenic cells is sort of a tautology. That’s what the entire field is based on. But in other diseases, we think that it’s a missed opportunity outside of cancer and maybe a little bit autoimmune disease. There are virtually no drugs that directly eliminate cells. Instead, what most modern pharmacology does is modulate individual pathways or proteins within the cells that drive disease, the pathogenic cells. But cells are complex networks, and because of that their behavior can be difficult to change via the modulation of single targets. And so we believe that it will be more effective to eliminate entire pathogenic networks, that is entire cells.

Grant Belgard: [00:02:02] So once you’ve identified a pathogenic cell for a particular indication, how would you go about eliminating them?

Adam Freund: [00:02:10] So our approach primarily focuses on using cell surface factors to drive biologics, antibodies generally to those cells and deliver cytotoxic activity. We’re really lucky actually that the cancer immunotherapy field over the last ten years or so has done this incredible job of creating a modular, programmable, therapeutic toolbox for eliminating specific cell populations. And unlike previous generations of cancer therapy, which were chemotherapy and were based on the internal metabolism of cells, these new tools are based on cell surface markers, which means they can be used any time you have a unique or enriched cell surface marker. And so that’s what we do. We think that the potential of these immunotherapy tools, multiple different modalities within this space are applicable and have really amazing potential outside of oncology. And that’s what we’re trying to bring to the to patients.

Grant Belgard: [00:03:08] So how would the regulatory pathway look for that?

Adam Freund: [00:03:11] It should look like most other biologics. As with anything, we will be developing the antibodies. We’ll be doing a lot of preclinical testing for efficacy and safety and then we will be registering for an I&D and moving into a phase one where we’ll be looking at ascending dose safety things like that. And then in phase two and three, looking for efficacy. One of the things that we will be focused on from a mechanistic perspective is making sure that the drugs that we’re developing are, one, eliminating the cells that we want them to eliminate, and two, not eliminating a bunch of other cells that we don’t want to eliminate. And then of course, we’ll have biomarkers related to that. And then we’ll also be looking at the efficacy readouts, which is to say, do we actually make the patients better and healthier.

Grant Belgard: [00:03:58] How do you think about animal models in this kind of work?

Adam Freund: [00:04:03] I think about them a lot because I think we all know that they are highly imperfect. A lot of the failures of drugs in the clinic can be attributed to poor preclinical models. And if you think about the way that we develop and evaluate preclinical models as a field, it’s sort of easy to understand why, especially when we’re talking about rodent models, mouse or rat models. What we usually do is based on some general understanding of the human disease, guess at a set of interventions, either genetic or environmental that might cause similar problems in the rodent. And then we assess histopathologically. That is to say, we look at a slice of the tissue and in a usually pretty subjective way, ask whether the tissue now looks like, the tissue from a human disease patient. And the issue with this is that it’s quite qualitative. It’s quite subjective and it usually doesn’t involve a large sample size. And so consequently, when we assume that because an intervention works in a rodent model, it will work in the human model, we’re often disappointed, At Arda, we can’t solve the entire preclinical model problem via biotech. I think this is a real issue and it’s something that I think the field needs to grapple with. But really at the end of the day, there’s no substitute for testing in humans. And that’s not something that we can get around. However, we can I think do a little bit better than the current status quo.

Adam Freund: [00:05:29] And that’s because when we compare human disease to preclinical models, we do so at the single cell level. So I haven’t really mentioned this up to now, but we’re really focused on using single cell data to identify pathogenic cells. And what that means is that we look at human data at the single cell level, usually single cell RNA-seq data. And we also look at single cell RNA-seq data from rodent models of the disease as well as other types of preclinical models. And in that high dimensional single cell space, we can compare and contrast models to the human disease. So we can look for the overall cellular architecture of the disease, the overall transcriptomic similarity. We can look at whether our specific cell populations are present in the disease, the populations that we find in humans. We can ask whether they are also present in these preclinical models. And then lastly, when we eventually hone in on a specific target, something that’s on the cell surface of the cells that we want to eliminate, we can ask whether the expression pattern of that target is similar in preclinical models as it is in humans, which tells us whether some of the safety and efficacy data will be translatable to humans. And so combined, we actually think that this will allow us to select better models, maybe even develop better models and better models lead to better drugs.

Grant Belgard: [00:06:44] When you talk about pathogenic cells, is it usually the case that a pathogenic cell state is accompanied by an unusual accumulation or depletion in the relative abundance of that cell type or do you see those things as quite unrelated? So I’m thinking here of something like fibrosis, right? I mean, you certainly have a change in the abundance, but then also concomitantly in the state and likewise with Microglial activation proliferation, is that the rule more exceptions that come to mind.

Adam Freund: [00:07:23] So I think that if we’re talking about a state, a cellular state that only exists in the disease context, then sort of by definition that state is accumulating. Now, it might not be accumulating because cells are actively dividing. It might be accumulating because cells are shifting from one healthy phenotype to an aberrant phenotype. And that could change how much we expect cell elimination to work. So one of the things that we think about is that not every disease is a good target for Arda’s strategy. Examples would be sarcopenia or neurodegenerative disease. These are diseases mostly of cell degeneration. And that’s not a context where eliminating more cells is likely to cause benefit. However, there are many diseases, inflammatory diseases, fibrotic diseases, other kinds of local tissue remodeling diseases where we do think that eliminating cells can either help the tissue restore balance, can trigger even in some cases regeneration, or can break a positive feedback loop that is causing that tissue to remain diseased. And so one of the ways that we carefully choose our indications is by assessing based on everything we know about the disease as well as the single cell data, do we think that there’s a cell population here that is causal? And if we have a reasonably strong hypothesis that the answer is yes, then we can go and more deeply characterize and investigate the single cell data.

Grant Belgard: [00:09:03] How many pathogenic cell indication combinations would you say are pretty much off the shelf based on the existing literature, you have pretty high confidence that eliminating the cell type would causally change the course of the disease for the better? And how much do you have to put into novel target identification, which I guess in your case is curiously kind of a combination of cell types by specific surface markers, right?

Adam Freund: [00:09:39] That’s exactly right. When we think of target identification, we think of two layers. There’s the layer of, can we find and identify the cells based on mostly their transcriptional signature and their enrichment in disease. But then can we find specific cell surface targets on those cells that can be used to eliminate them and not healthy cells. So that’s exactly right. And to your question about how many indications is this sort of do we expect this to be a useful strategy? We actually think this will be quite broad. And partly this has been driven by what we’ve seen in the single cell literature over the last five or so years. So as single cell data has accumulated, we’ve seen huge numbers of papers coming out where people will examine a disease, usually from human patients for the first time using single cell data. And they almost always ask the question, do we find cell states that are enriched or unique in the disease state and that appear causal? Correlation is not causation. So just because a cell state is enriched in disease, doesn’t mean it’s bad. It could be adaptive. In the case of if you’re looking at normal wound healing, the presence of myofibroblasts is adaptive. It’s helping that wound heal. But in the case of fibrosis, it’s maladaptive. And so there’s a little bit of biological inference that has to happen here.

Adam Freund: [00:11:00] But by and large, finding a cell state or multiple cell states that are enriched in patients and not really present in controls, and that those cells express genes or factors that are thought to be causally pathogenic based on the understanding of disease, it appears to be the rule rather than the exception across tissues, across cell types, across indications, across groups as well multiple groups from all over the world who are doing this kind of work are finding the same thing again and again. And as we’ve compiled data sets that have been produced by these groups, we find the same signatures again and again. And so we really do think that this is quite a broad space. To be specific, the initial areas that we’re exploring really because we find one, a strong therapeutic hypothesis and two, quite a lot of single cell data already available. And those are fibrotic diseases and as I mentioned, inflammatory diseases. So some autoimmune diseases, other sort of local inflammatory diseases and so that’s where we’re starting. But eventually we plan to expand to multiple other indications and hopefully ultimately aging itself, which we think of as being driven in part by a chronic inflammatory process that has its roots in the accumulation of pathogenic cells.

Grant Belgard: [00:12:20] And how do you see the work that you’re doing now building up to tackling aging more broadly? Do you see those as completely distinctive programs with no overlap, or do you think a lot of what you’re doing now can feed into that?

Adam Freund: [00:12:33] I think a lot of what we’re doing now can feed into it, especially on the inflammatory disease side of things, because that’s our best hypothesis for how this kind of approach might impact aging. And that could change over time, of course, as we learn more. But one of the things I’ve often focused on when thinking about aging and just to clarify, I’ve studied aging for quite some time. I’ve been fascinated by this topic ever since I was in graduate school and I first came across the idea that aging is not just unavoidable wear and tear. It’s not just the accumulation of entropy in some physical law kind of way. It’s actually a process that can and is modulated by genes and biology across the entire animal kingdom. Once you believe that aging can be modified, it’s hard not to get excited about studying it. And so I’ve been fascinated by this for many years. And one of the things that people in the aging field think a lot about including myself is how do we develop a drug for aging. And there’s two kinds of drugs that one could imagine, a drug that slows down aging. Every year you take it, you only age half as much as somebody who’s not taking it. And then a type of drug where you reverse aspects of aging. The first one poses some serious problems from a clinical trial perspective in that if primarily what you’re doing is slowing down the aging process, the earlier that you start dosing, the better.

Adam Freund: [00:13:57] First of all, in terms of a person’s life, which means the healthier they are, which means the more liability any safety signal has, and the longer your clinical trials have to be because you’re effectively waiting for your control group to age. And then you’re hoping that your experimental group doesn’t and that can take years depending on how many people you have in your study. It could take many, many years. In contrast, the idea of reversing certain aspects of aging is a lot more tractable because in this case, you’re now looking for your experimental group to get better and your control group to basically just stay the same. And depending on the mechanism, theoretically this could happen in elderly people who already have experienced some degenerative changes as well as in younger, healthy people and really I think the only reason people aren’t more focused on finding this latter type of intervention, these age reversal processes as opposed to age delaying processes, is that I think there’s an assumption that it’s harder. It’s harder to turn something back than to stop it from happening in the first place. But I don’t actually agree with that. I think that if you imagine a biological process that’s been tuned over millions, billions of years of evolution, the idea that we’re going to be able to tweak it just enough so that it works even more efficiently than it already does and so we age just a little bit slower or maybe even a lot slower than we already do, that we’re just going to be able to tune homeostasis to be perfect such that we never decay.

Adam Freund: [00:15:25] That to me sounds quite challenging. Imagine building a car where it never needs service, right? It just runs perfectly forever as opposed to a car where you recognize it’s going to break down and you just know that every year you’re going to take it into the shop and do a full tune up. The latter approach to me actually seems quite a bit more tractable. And so one of the reasons why I’m excited about Arda’s approach is that it fits squarely into this reversal camp in that what we are trying to do is to identify cells that over time accumulate with age and that cause detrimental tissue changes. Once we find those cells, if we eliminate them, we’ve effectively set the clock back at least for that particular process. And we don’t think that this will cure every aspect of aging. There are some parts of aging that really just probably need to be addressed using joint replacement or other kinds of non-pharmacological interventions. But for many things including those caused by the accumulation of chronically inflamed cells, I think that eliminating those populations could be a really effective path to treatment.

Grant Belgard: [00:16:25] Are there companies in this space taking this approach?

Adam Freund: [00:16:28] So there are companies that overlap with Arda in specific areas, although none that we know of are taking an identical approach. Perhaps one that people in the aging space might be most familiar with are companies that target senescent cells. Essentially senescence is a cell state that different types of cells can enter in response to damage or other external stimuli. It’s traditionally been described as an irreversible cell cycle arrest where the cells can no longer divide. And we found empirically over the years that we’ve been studying this process that in addition to not dividing, they also upregulate certain inflammatory processes and pathways. And when this was discovered, it launched a series of companies that thought that if we eliminated these cells, that these might be the sort of wellspring of age related changes and that eliminating them might reverse some of these changes. And that hypothesis had a lot going for it, and it still does to some extent. However, we’re learning that the senescence state has been mostly characterized through in vitro cell culture experiments and has not translated super well to the in vivo setting. And we’ve seen some clinical trial failures in this space and I suspect we’ll see more before the day is out. Therefore with Arda, we’re trying to do is go the other direction. We’re starting with patient data and letting the data tell us which cells to eliminate and how to eliminate them, rather than starting with a predetermined disease hypothesis about what the state of those cells should be. But from maybe a 30,000 foot view of the general aging space, I think that it sometimes seems like what we’re doing and what some of these companies are doing have some similarities. And to the extent that we’re both trying to find bad cells and eliminate them, there are some similarities. But I think that there’s a really important distinction there as well.

Grant Belgard: [00:18:21] So tell us about your path to founding Arda, because you’re a solo founder, right?

Adam Freund: [00:18:28] That’s correct, yeah. I left my previous role and started Arda as a solo founder.

Grant Belgard: [00:18:34] So what? It’s obviously a pretty huge leap to take. I’m sure you had a lot of scientific confidence that had been building over over the years that led to that. So can you tell us about how that journey looked?

Adam Freund: [00:18:48] I would be happy to. I really was thinking about Arda and ideas related to cell elimination for a long time before I ended up starting the company, almost going all the way back to my graduate work. So did my graduate work with Judy Campisi, studying of all things cell senescence, and it was in that lab that I was first exposed to the idea that eliminating these cells might be a good thing. And in fact Unity, the first senolytic company was founded essentially right in Judy’s lab while I was there and grew after I left. And that was really exciting thing to see. After the cell senescence work in my graduate school, I went to Stanford where I did my postdoc studying telomerase biochemistry. So also trying to understand more about the processes related to aging. And again, I continued to think about telomere shortening is one of the major causes of cell senescence, at least in vitro.

[00:19:43] And so I continued to think about this idea of are these cells accumulating? If so, what are the processes? And then when I got to Calico, which was my role after my postdoc, there I was a principal investigator and a scientific lead on a few drug development programs and in my lab, we spent a lot of time thinking about how to represent organism state and cell state from high dimensional data. And I kept abreast of the cell senescence literature, watched how that field evolved and kept thinking about how we might be able to use high dimensional data to develop new therapies and eventually came around and saw a few other interesting proof of concept papers coming out from different academic groups where instead of targeting senescent cells, they were targeting fibroblasts in certain kinds of fibrosis or microglia in neuroinflammation. And this idea just developed that maybe we could do this in a more systematic and deliberate way and ride this wave of single cell data, because it really is. Single cell data allows this to happen in a way that we never were able to do it before. So for decades right since the advent of microarrays really, we’ve been able to measure the expression of every gene in the genome at a bulk tissue level, and that let us find which genes were most upregulated in disease. And it turned out that this was a pretty good place to start for finding targets. As mentioned earlier, correlation is not causation, but if you pick the top 15 most upregulated genes in a diseased tissue, chances are some of those are causally pathogenic.

Adam Freund: [00:21:18] But we didn’t have something like this for cells. If we wanted to understand which cell populations were enriched in disease, we had to do this very biased search using a handful of markers and then assessing via [] FACs. And consequently the resolution we had was extremely limited. We could talk about fibroblasts versus Myofibroblasts or we could talk about M1 and M2 macrophages, but that was really about it. And now we can see right with the advent of single cell data and the amount of data being generated, we have cellular catalogs of disease at unprecedented resolution. So although I had been thinking about this idea of eliminating pathogenic cells for a long time, it was only really when the technology reached the stage we’re at now that this became actionable. And so when that happened, to me it didn’t really seem like a big leap to say, well let’s combine single cell analysis with the tools of immunotherapy and let’s see what we can do. And that’s when I finally decided to take the leap and start Arda.

Grant Belgard: [00:22:21] Since Arda was your first biotech startup, what surprises did you encounter along the way?

Adam Freund: [00:22:30] With any origin story, there were some fits and starts along the way. As you mentioned when I started Arda, I was starting as a solo founder and I was leaving my current role at a biotech company and starting, and that meant that really I started with very little. And so it was just sort of me and a pitch deck really. I mean, there was no data that I owned because I couldn’t take anything from my previous role, nor was there anything really relevant from my previous role for the company. I didn’t have an academic lab where I was spinning something out of, and I don’t think I appreciated at the time how rare that was in the biotech world. It turns out that most biotechs start in one of two ways. They’re either spinning out of an academic institution. And so there’s a whole body of data and there are papers that are directly relevant, and there’s perhaps even a scientific advisory board already in place, or they come out of these venture creation firms where in a similar way they’ve been incubated with a team that has generated a bunch of data supporting a hypothesis.

Adam Freund: [00:23:36] And only once they’ve reached a certain level of empirical confidence in the overall idea have they launched. I didn’t have either of those things. And one of the pieces of pushback I got a lot when I was initially raising was just why do you think any of this is going to work? I mean, my pitch deck was full of examples from the literature, but it wasn’t my data. It was other people’s data. I had a few computational analyses I had run that sort of suggest that this could work. But by and large it was pretty bare bones and it really took a lot of talking to different investors before I found investors who were willing to take both on the idea, but also really, frankly, on me because there wasn’t much else to bet on at that point. I’m really fortunate to have the investors that I have. And so the round did eventually come together at the sort of end of 2021. But it was scary for a while there. It did not come together as fast as I had hoped it would.

Grant Belgard: [00:24:32] And you joined the On Deck Longevity Biotech Fellowship in the fall of 2021. How have you found that?

Adam Freund: [00:24:40] The On Deck Longevity Biotech Fellowship? That’s right. So how did I find that? Nathan Cheng, who runs on the On Deck Longevity Biotech Group, reached out to me. I guess he found me through, boy I don’t even know, maybe some of my papers or maybe a contact. And it seemed like a great opportunity to meet other people who were at the stage of starting companies or considering starting companies that were focused on extending healthy longevity. And I think I joined that in 2021. It’s been a great opportunity and a great way to meet other people in the field and learn from other people who are further along in their startup entrepreneurial journey than I am. And that really has been powerful. Also I should say that that’s been powerful in a lot of other contexts as well. So On Deck is one group that I’m a part of, but I’m also through my investors and through other organizations and part of other groups of scientists, mostly who have started companies or who are early at biotech companies. And it’s really helpful to be able to learn from other people’s experience. There’s so much to know about starting and developing companies that I didn’t know, and there’s so much I still don’t know. But being able to ask questions and get advice allows you to shortcut a lot of things, even something as simple as, Hey, what law firm should I use? How do I pay my employees? Or What’s a reasonable benefits package? I mean, you can go on the Internet and research this for two weeks, or you can ask the three founders you respect most and guess that if it’s good for them, it’s probably good for you too. There’s so many decisions like that. It’s incredibly helpful to be able to shortcut some of that stuff.

Grant Belgard: [00:26:20] What are other groups that you found helpful in that respect?

Adam Freund: [00:26:22] So let me look at my Slack workspace, because they’re all right there. So I found that the On Deck Longevity Biotech is one, Andreessen Horowitz, our lead seed investor, has Biohealth community. They also have email lists that are incredibly helpful that bring together, by the way, people who aren’t just in bio. There’s also a lot of people who are in tech and health tech and crypto, and it’s really interesting to see which lessons they’ve learned apply to bio and which don’t because they don’t. Bio is a different animal in a lot of ways, but there are also some consistent patterns and ideas around starting and growing companies that cross sectors. There’s also the Village global community, which is another one of our investors. They provide a space for founders and entrepreneurs to discuss ideas like this. And then there’s a few longevity groups like Longevity SF, which I’ve recently joined and again is more focused on the aging side of things, which always fascinated me. So it’s just helpful to have these communities because it can be when you’re just starting out, your company is very small. There’s just there’s not a lot of people to talk to so having these communities in place can be very, very helpful, both professionally because it allows you to sort of network, but also just psychologically. Because it can give you the feeling of a community which it’s otherwise hard to get from a company of just a couple of people.

Grant Belgard: [00:27:38] If you could go back to send a message to yourself in the summer 2021, what would that message be?

Adam Freund: [00:27:44] I think I would send a message to set my expectations appropriately. I would say it’s going to be hard to fundraise. And then when you eventually do fundraise, it’s going to be even harder to hire because once you know you’ve got the money, then you have to convince people to join you on your crazy mission. And it’s been a journey. And now we’re of course building traction and things are really moving. But it does take a certain degree of stoicism and staying the course and developing thick skin. I will say that too. I think one of the things that I have changed the most in the last year and a half, I’ve been doing this is that more people have said no to me in the last 18 months than in like the rest of my life combined. So I can’t tell you. And it’s not that anyone’s rude about it. I mean really honestly, venture capitalists sometimes get a bad rap, but found that the vast majority were professional and they were polite, but they were politely saying no. And that’s hard when you go to someone and you say, okay, so here’s the idea I have. It’s literally my best idea.

Adam Freund: [00:28:46] Like of all the things I think in this world, this is my best one and I want to spend the next X number of years of my life solely dedicated to making this work. And the person across the table from you looks at it and says, Yeah, I don’t think that’s a very good idea. That’s hard to hear, even if they’re being nice about it. And the first ten times it really hurts. And then you sort of grow calluses on your soul and it starts to hurt less and that sort of sounds like you go dead inside. And it’s not totally true, but it’s also not totally false because you have to be able to weather the nose. You have to be able to just smile, say thanks and move on and in a way where you’re not ignoring useful feedback. Because one of the most important things is you go through this journey is adapting to the feedback that you receive, but also not letting no cause you to stop moving. Because if you do that, you’ll never get to port. So you have to be able to weather the nose and I think that at this point, I’ve developed some pretty thick calluses.

Grant Belgard: [00:29:45] Yeah, well the good news I think on the hiring front is, at least from what I’ve seen as you grow and get better established and so on, that becomes easier and easier, right? It’s a lot harder to hire your first or second employee than it is to hire your 20th or especially you’re like 200th by that point. When people Google your company name, they won’t just find your company page. There will be articles about it. They can send it to their friends and family and have them not try to talk them out of joining such a young, seemingly unstable company, even though I think that’s often an unfair characterization. But it’s certainly a common perception nonetheless.

Adam Freund: [00:30:34] It’s so true. One of the things that I feel like we spend the most time doing as early founders and early employees of companies is building credibility. That’s all it is, right. Most people when you tell them about your idea for your company, they’re not judging the scientific merits of your idea. Not really. I mean, that’s part of it. But what they’re really doing is watching you and saying, does this person, are they a charlatan? Because most other people unless you’re talking to someone who’s also an expert in the exact same things that you’re claiming to be an expert in, they know that they don’t have the same expertise you have. And so they’re not going to sit there and say, well I’m going to argue with you about X, Y and Z in terms of the scientific details. What they’re trying to establish is, are the scientific details that this person is telling me reliable. Is this person trustworthy? Does this person have credibility? And there’s a million ways that we signal or don’t signal that we have that credibility. I was I think fortunate in that when I went out to do my raise. I had spent seven years at Calico, which had a great team from Genentech, Art Levinson, Hal Baron, Cynthia Kenyon on the Longevity space, and others who had created a company with a lot of credibility. And then before that was institutions that carried some credibility.

[00:31:43] So I was able to go into rooms and say, Look, I don’t have any data. I just have this pitch deck and this smile and somehow still at least give some indication that I was a real scientist who knew what I was talking about. This is one of the reasons why it’s so hard to hire early employees. I was very fortunate in that my first hire was a person who I had worked with actually. He was a postdoc in the same lab when I was a graduate student and he had gone on to actually work at Unity. He was there for eight years, was the first employee and understood the space really well, understood it probably better than me frankly and knew me. And I knew him and we knew we worked well together. So the first hire was reasonably straightforward. And that’s Remi-Martin Laberge, who is our vice president of research. But then after that, exactly as you said you’re meeting people who don’t know you and you’re trying to convince them that this is the thing they should bet their life in their career on for the next couple of years at least. And that can be hard. But as soon as you see that, oh, half a dozen people have made that same choice, it starts to seem a little bit less crazy.

Adam Freund: [00:32:48] And so then it gets easier. And by the time 20 people have made that choice, you’re like, oh, okay, this isn’t totally crazy. But what people don’t realize sometimes is that it’s sometimes useful to fight against that tendency because earlier that you get into a startup, the much more impact you can have and the much bigger upside there can be both professionally and financially if you ever look at a curve of the way equity dies off by employee number, it’s pretty substantial. And the probability of success doesn’t necessarily go up at the same rate that equity and options for career growth go down. In fact in many ways, if you’re joining a company that just raised a round of financing and they haven’t hired anybody so they haven’t spent it, that company is in better shape than a company that has just hired 15 new employees, spent the bulk of their A round and now needs to turn their attention to a B round within six months. So I understand why it happens, but I actually think there’s a lot of reasons to if being in the startup world is something that excites you, really try to pick companies not based on the credibility signals being sent by others, but based on your own assessment of whether that company is a good fit for you.

Grant Belgard: [00:33:59] And what factors would you weigh heavily in that? Because I think sometimes the kind of go to is there may not necessarily be the most predictive.

Adam Freund: [00:34:12] This is hard. This is a hard question. There are so many unknowns. Just like when you’re hiring for a role, you’re trying to learn as much as you can about this incredibly complex person who’s sitting across the table from you in 30 minutes. There’s only so much information that you can gather. And the same thing is true when it’s in the other direction. And here you are a candidate trying to decide which startup or which company you’re going to join. So if you are a scientist, of course the science. As much as you can dig into the science, pressure test it, ask the questions, and if you get any sort of defensiveness as a response or anything like that, that’s very concerning. If you get a lot of, well, we can’t talk about it because it’s super secret. Personally I think that’s also concerning. I think that generally people secret sauce is not as secret or as delicious as they think it is. It’s more about like execution ideas are cheap. So definitely on the science side. But then also I would look for how thoughtful the people at the company are, especially the leadership about building a culture and an incentive structure that are carefully designed. I think sometimes there’s this idea that startups can just be these places where it’s a little bit of the Wild West and everything just sort of works and clicks together.

Adam Freund: [00:35:31] And that might be true up to something like ten people. But once you get above that, the laws of human interaction assert themselves in ways that are difficult to predict and often not what’s best for the overall growth of the company unless there are processes and systems and a culture in place to realign people. And it’s amazing when this goes right, because startups do provide this incredible opportunity to have everyone rowing in the same direction. One of the things that that I think a lot about is for any person in any organization, there’s this question of how they should prioritize their activities. And in many cases, what’s best for that person is not what’s best for the organization. Think about middle manager at some large pharma company who’s they have stock and they have an individual performance bonus, but they don’t really have the ability to impact in a huge way the outcome of the company. They can do it in little ways. And if the company is wildly successful, it doesn’t directly impact them by a lot. What matters more to them is their individual base salary, their bonus and their title. And so you get a lot of internal politicking and people working on these sort of local optimization problems.

Adam Freund: [00:36:45] And if every person at the company is doing that, it’s only by chance that that comes up to a point where it’s actually benefiting the organization as a whole. And it’s almost certainly not the most efficient way one could do that. And the alternative is at a startup. The best way for every person at a small startup to succeed both professionally and financially is for the company to succeed. It doesn’t make any sense to work your way up the corporate ladder of a six person company to become the vice president of nothing. And then the company tanks and you have to go get another job. It makes a lot more sense is to say, I’m going to spend every waking minute trying to make this idea, this company actually work. Because if that happens by virtue of me being early, I will have so much potential. I’ll have so much experience. My equity will be worth so much. There’s all this stuff and that creates alignment. And alignment is so hard to create otherwise. And so to me, that’s really important. But you have to put these other processes into place. You think carefully about this because the bigger you get, the harder it is to maintain that alignment.

Grant Belgard: [00:37:45] And once lost, it’s hard to regain.

Adam Freund: [00:37:47] Oh, completely. Absolutely right. And I mean like one or two people can act as dominant negatives and people take their cues from others about what’s appropriate and acceptable in an organization so it’s really important. And this makes or breaks companies. And so if I were evaluating different startups or different companies, I would look really carefully at the incentive structures and how they’ve been designed and how thoughtful people are about them.

Grant Belgard: [00:38:12] It’s really insightful. Thank you so much for joining. It’s been a really great conversation.

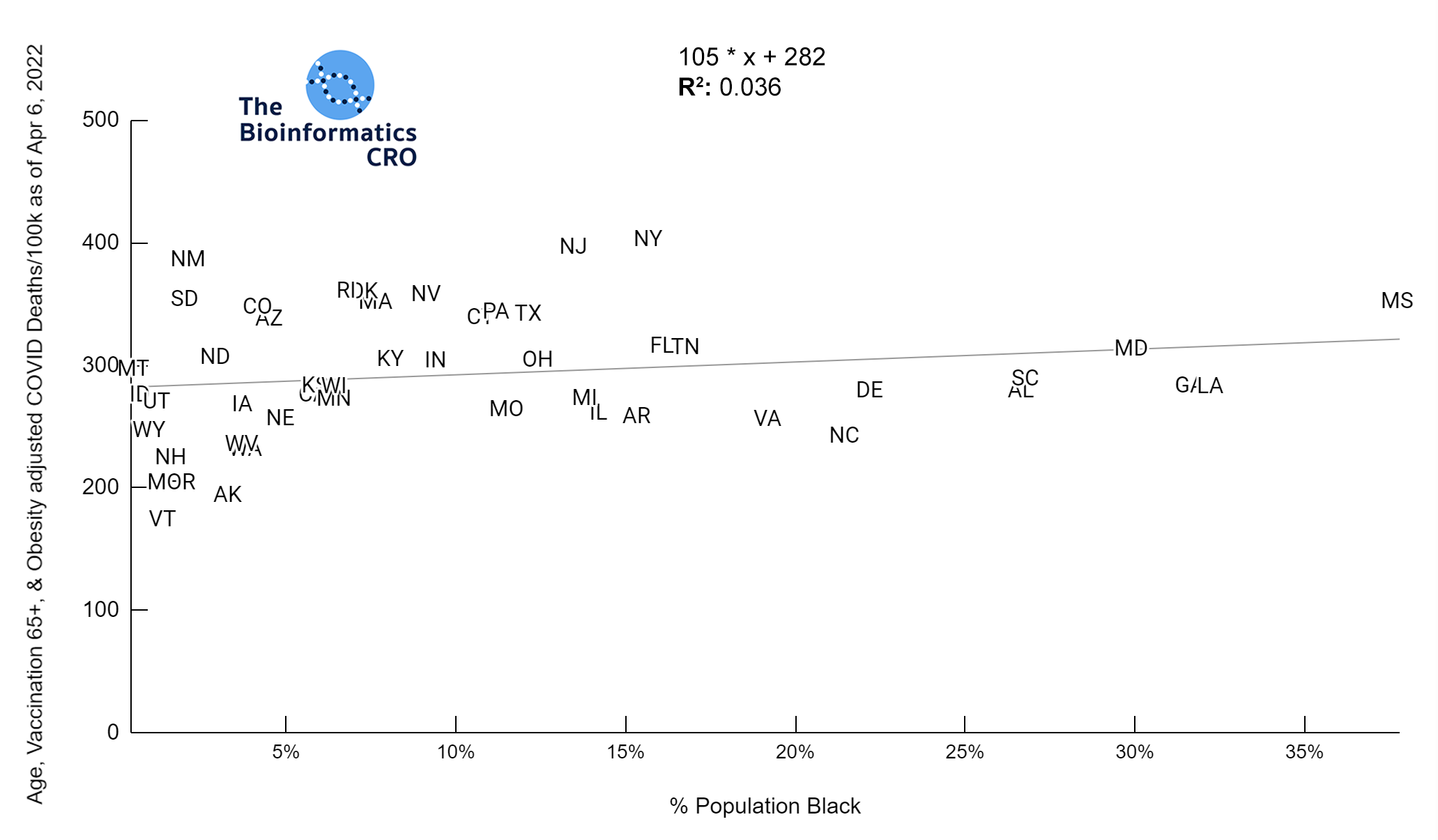

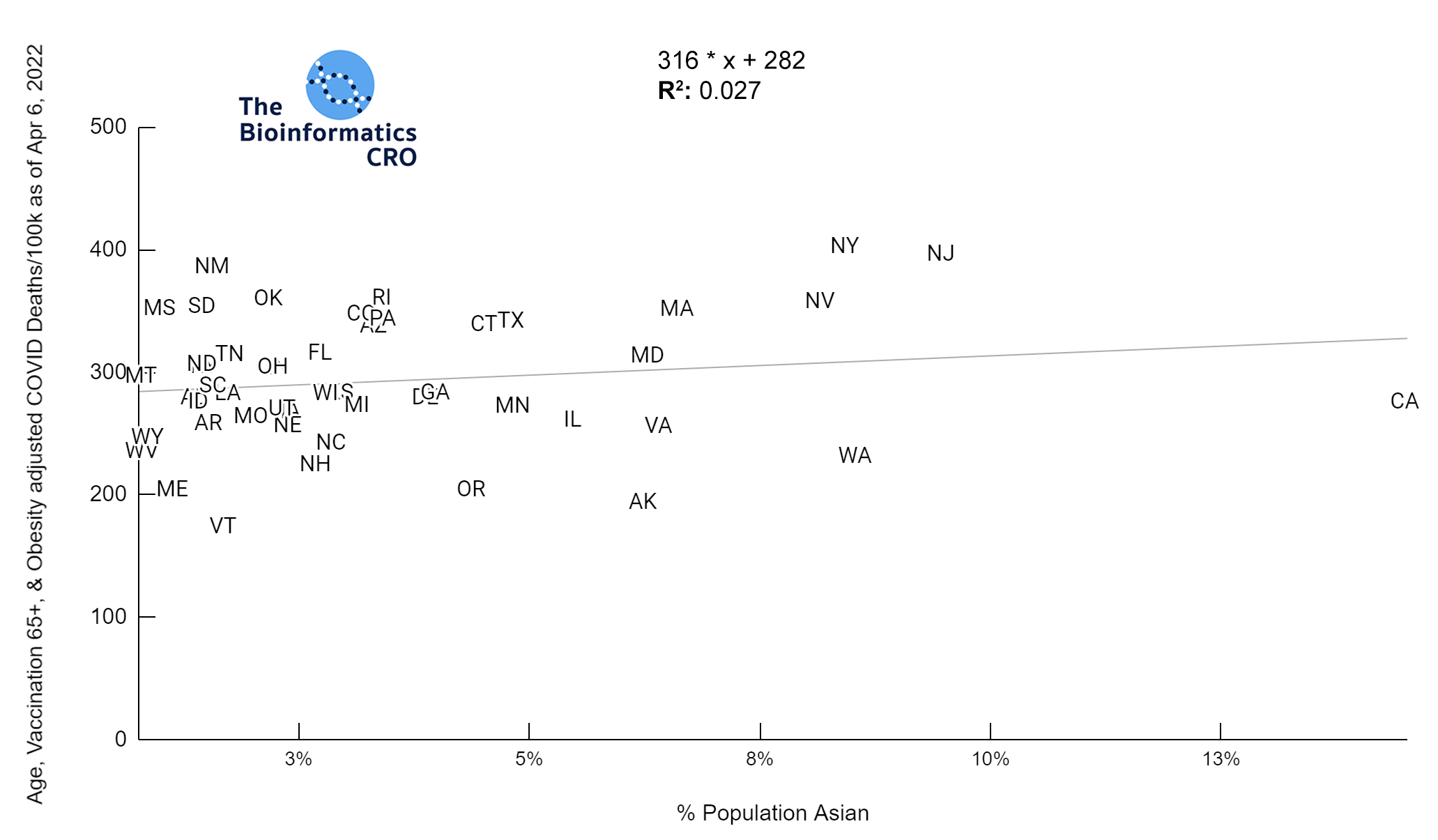

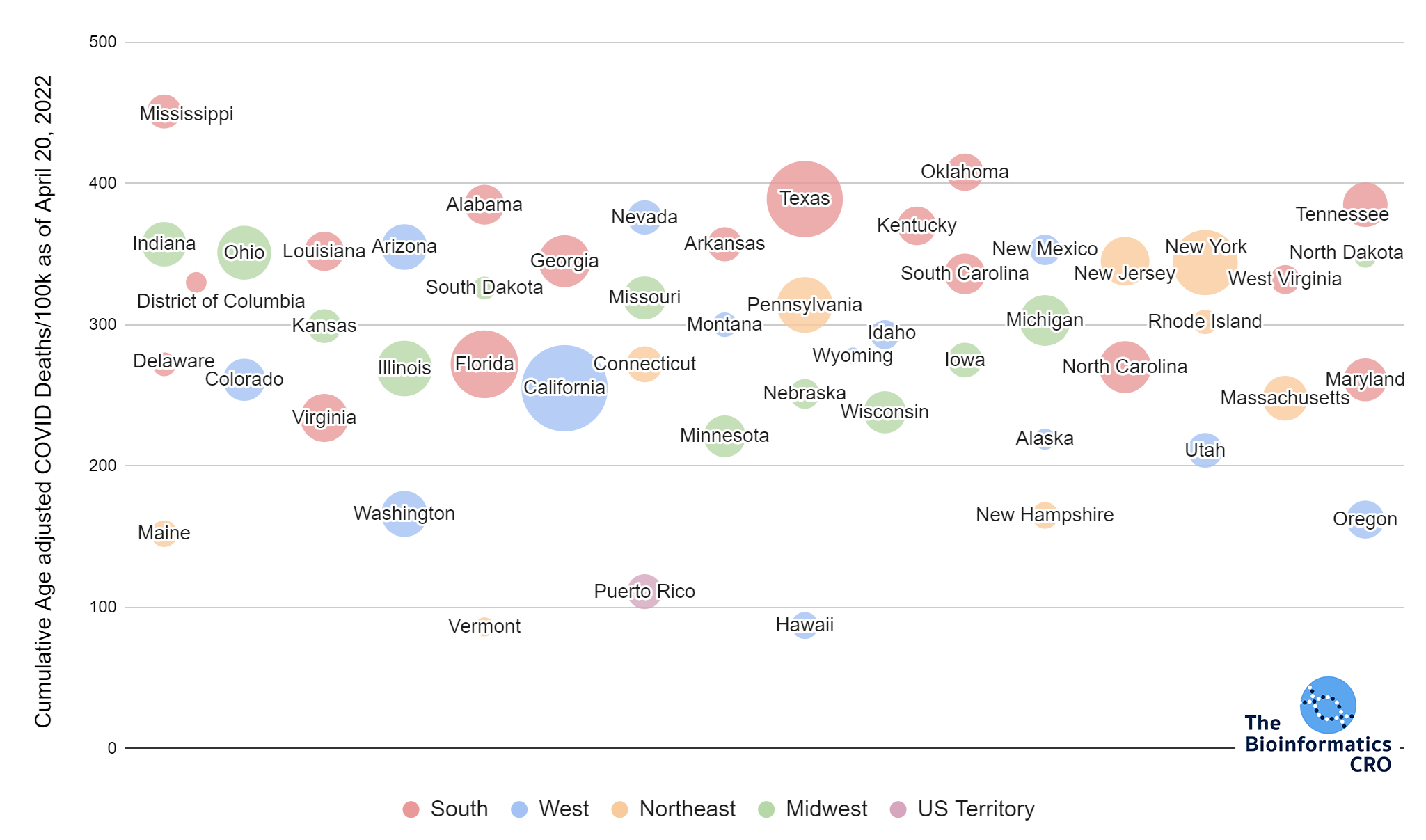

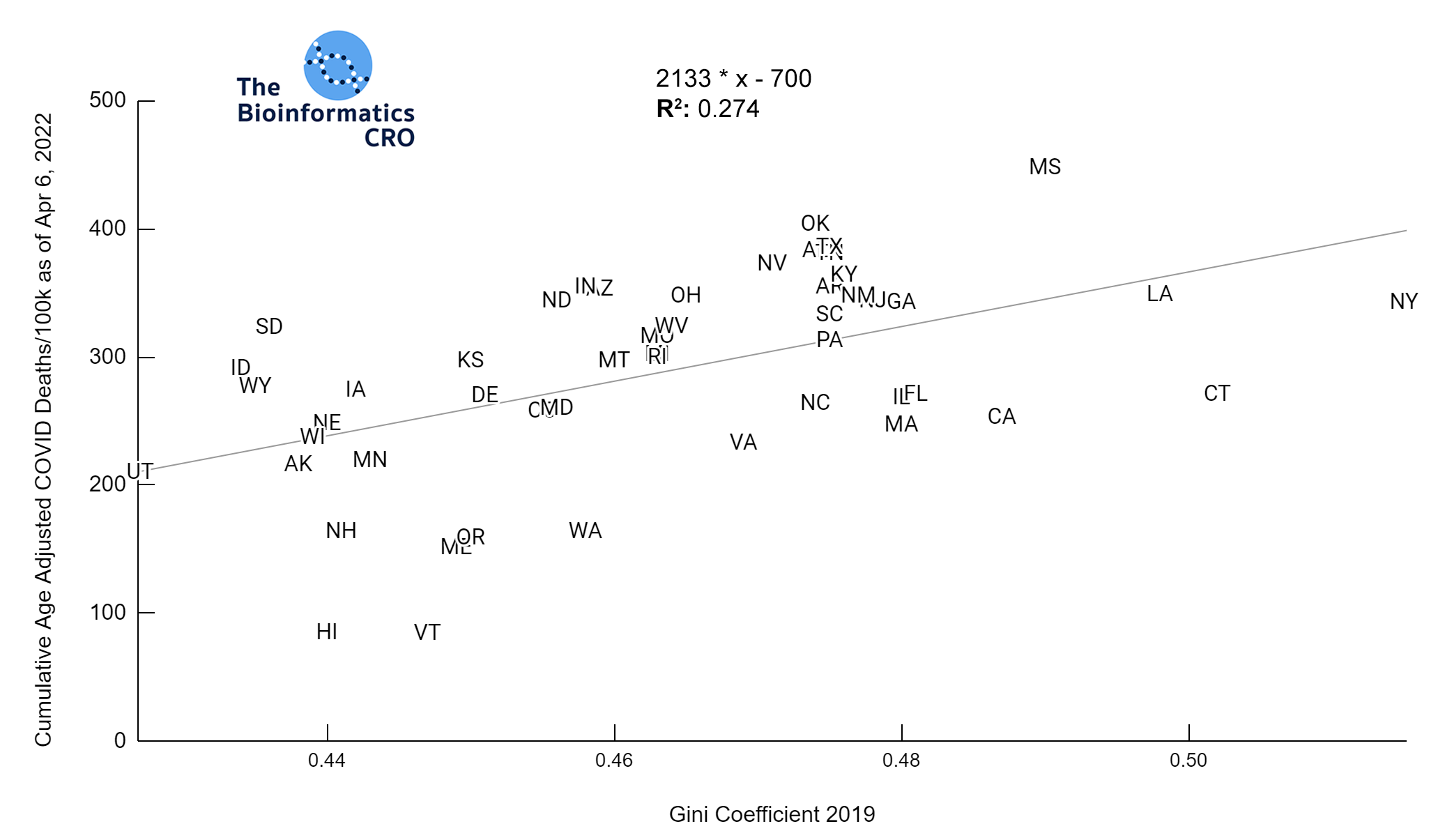

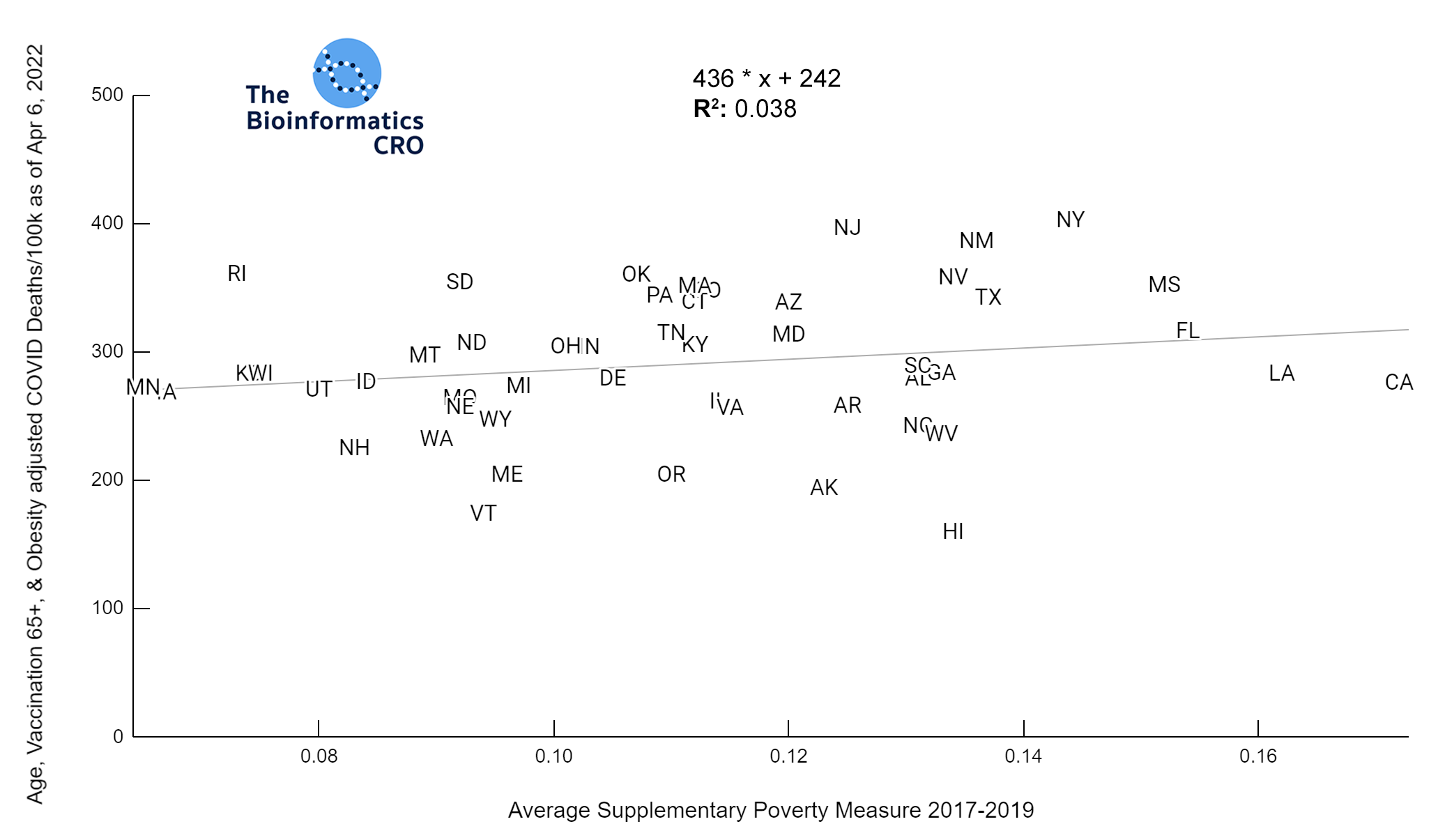

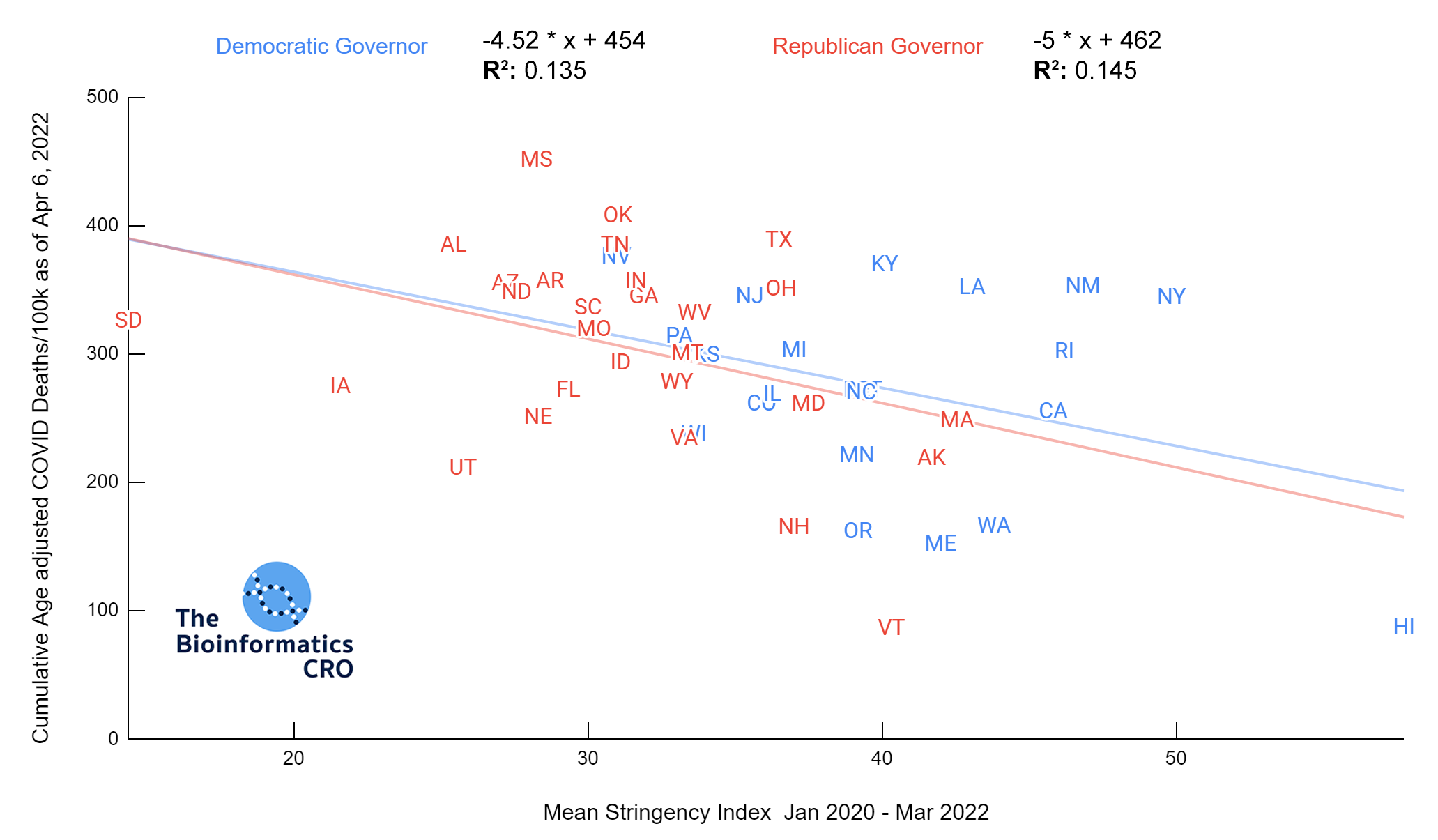

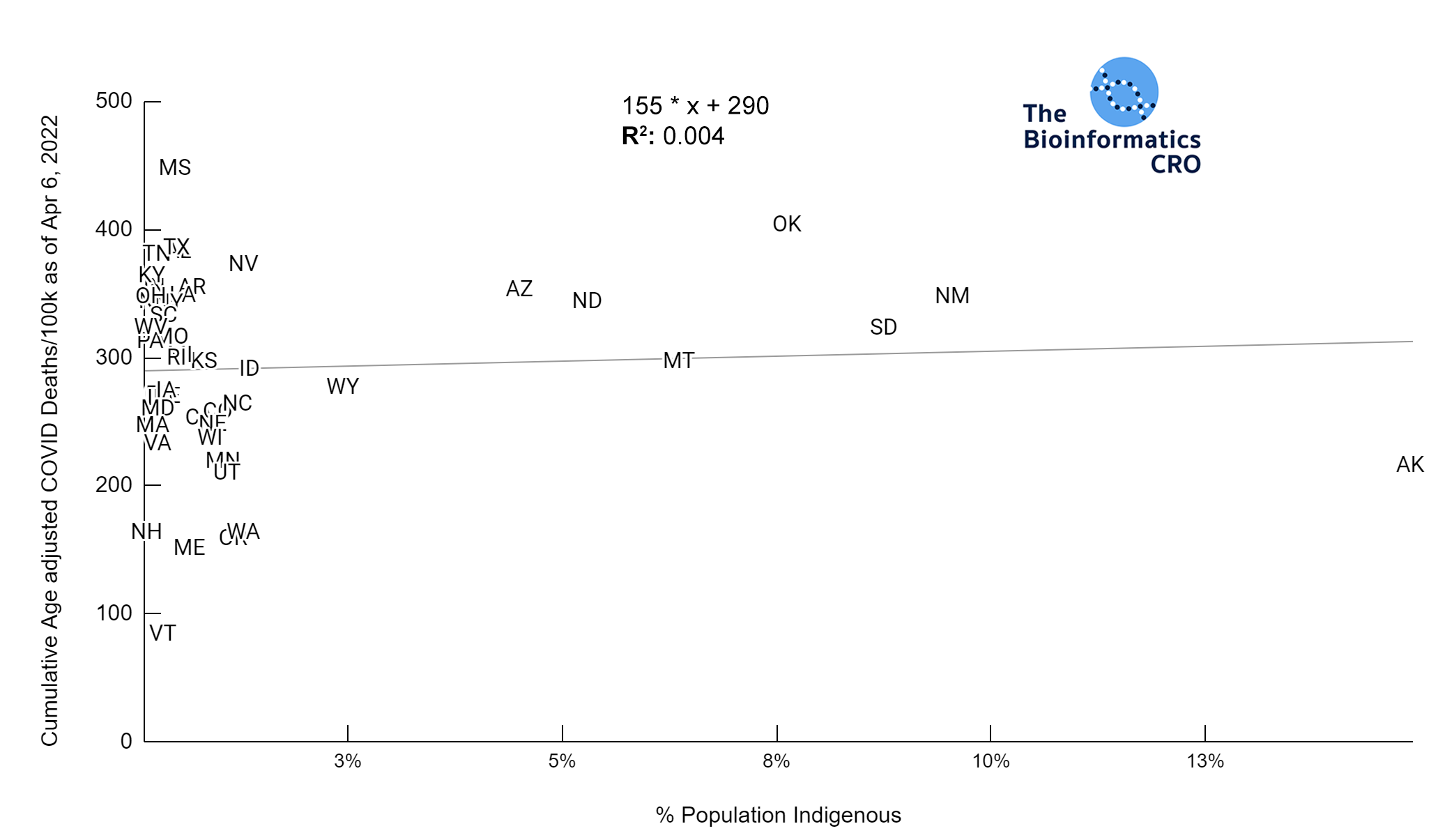

It should be noted that the race and ethnicity data are not normally distributed (Shapiro Test P<0.01 for all).

White P<0.01 | Black P<0.01 | Asian P=0.22 | Indigenous P=0.66 | Hispanic P=0.30

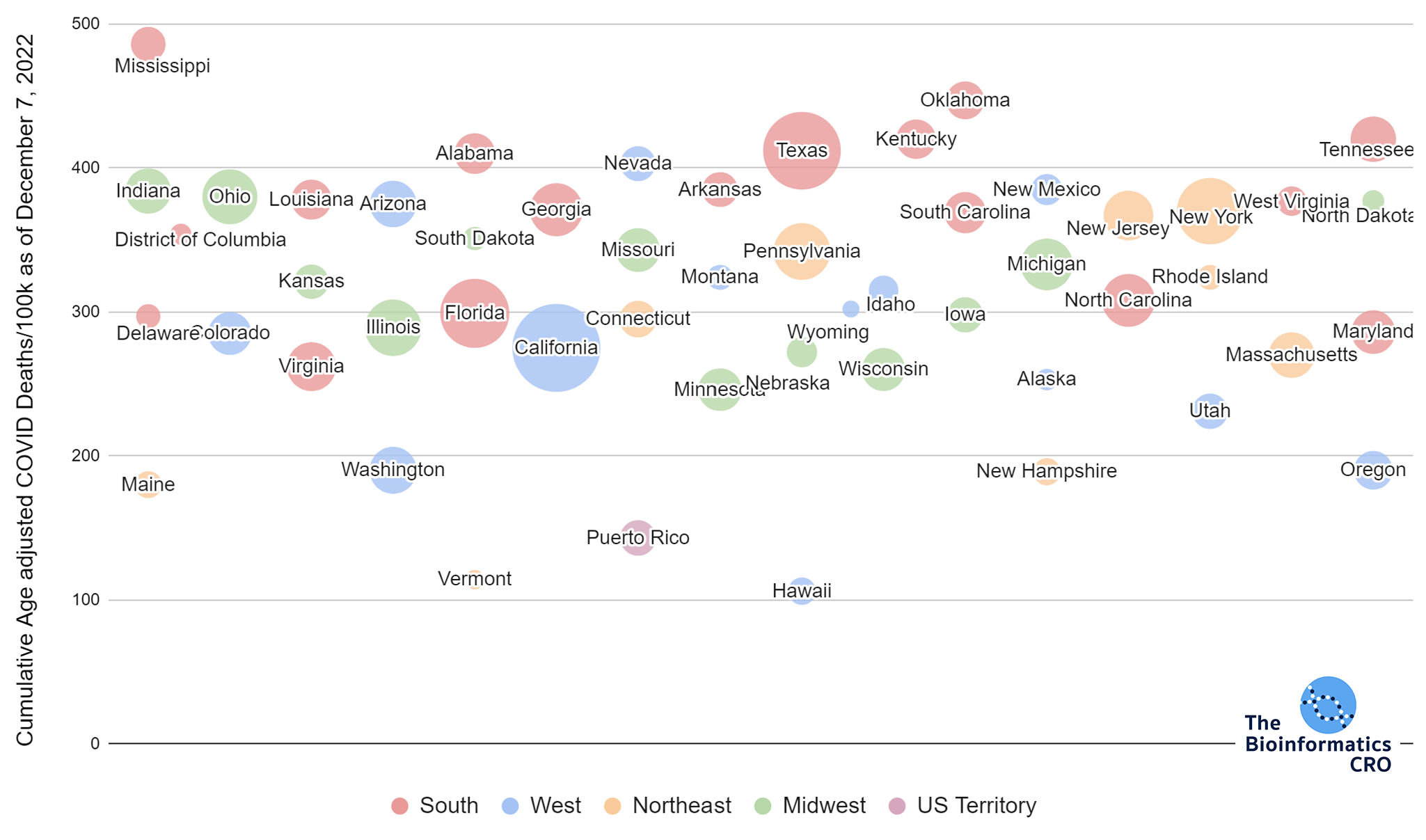

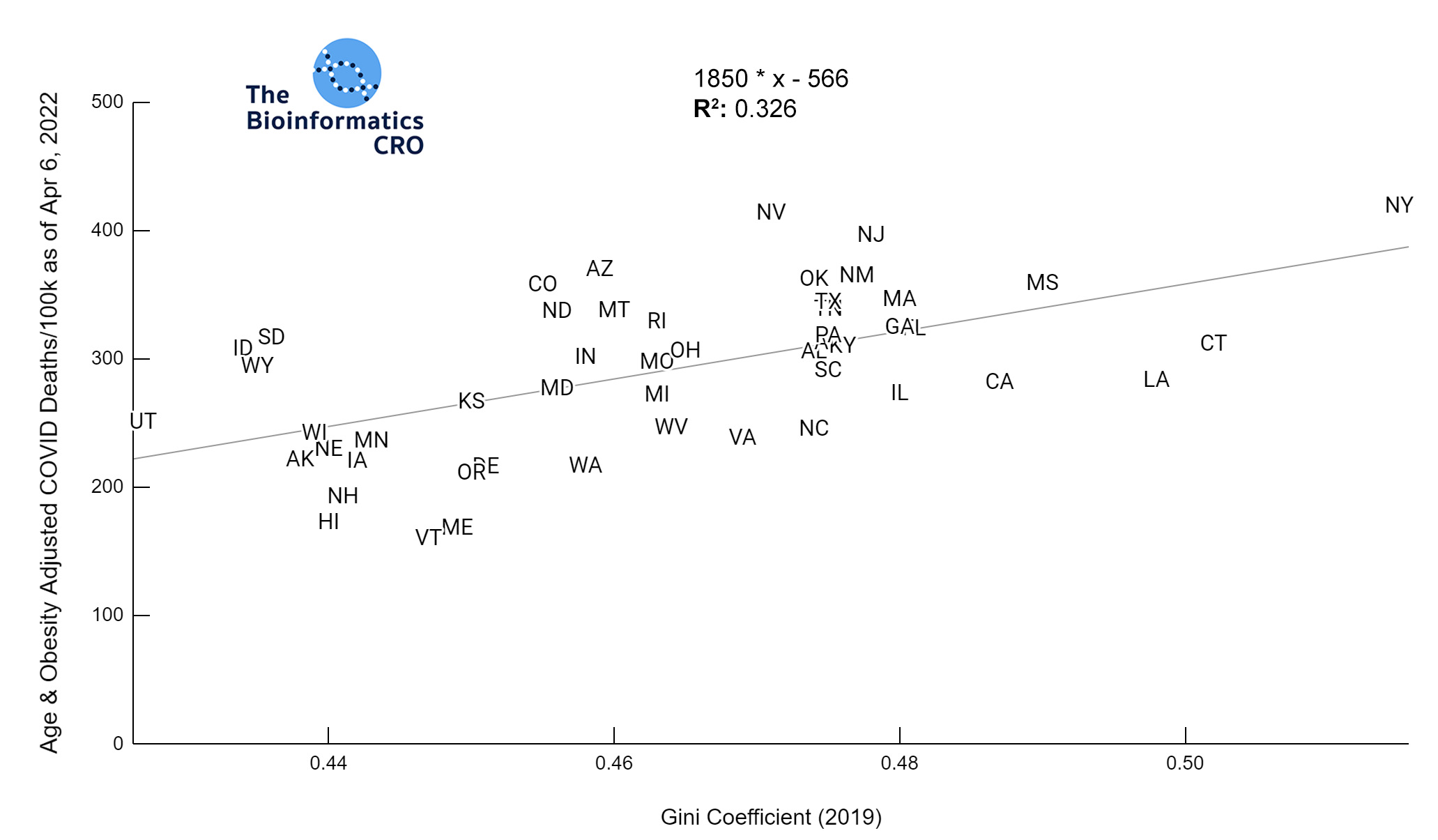

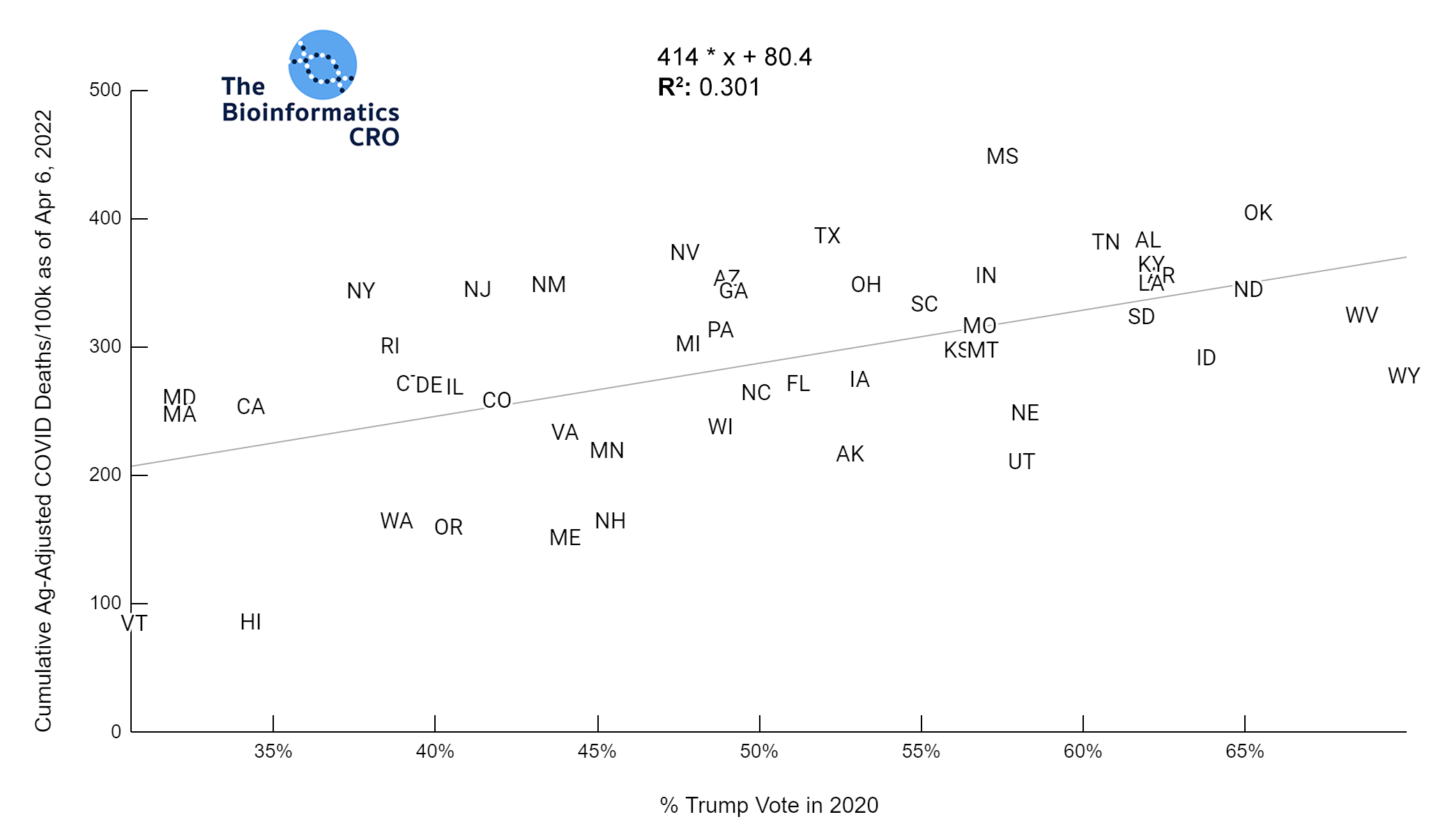

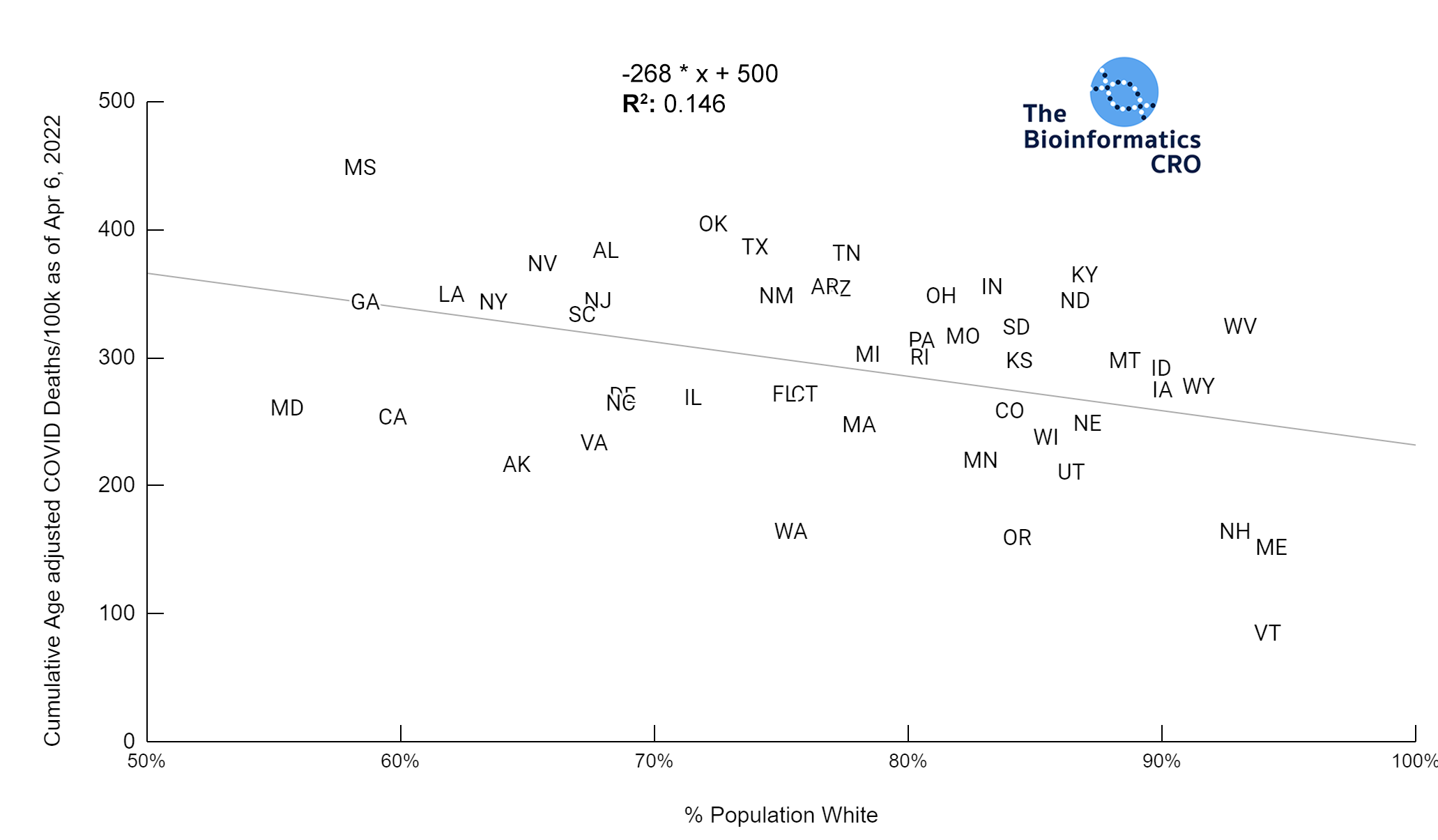

It should be noted that the race and ethnicity data are not normally distributed (Shapiro Test P<0.01 for all).

White P<0.01 | Black P<0.01 | Asian P=0.22 | Indigenous P=0.66 | Hispanic P=0.30

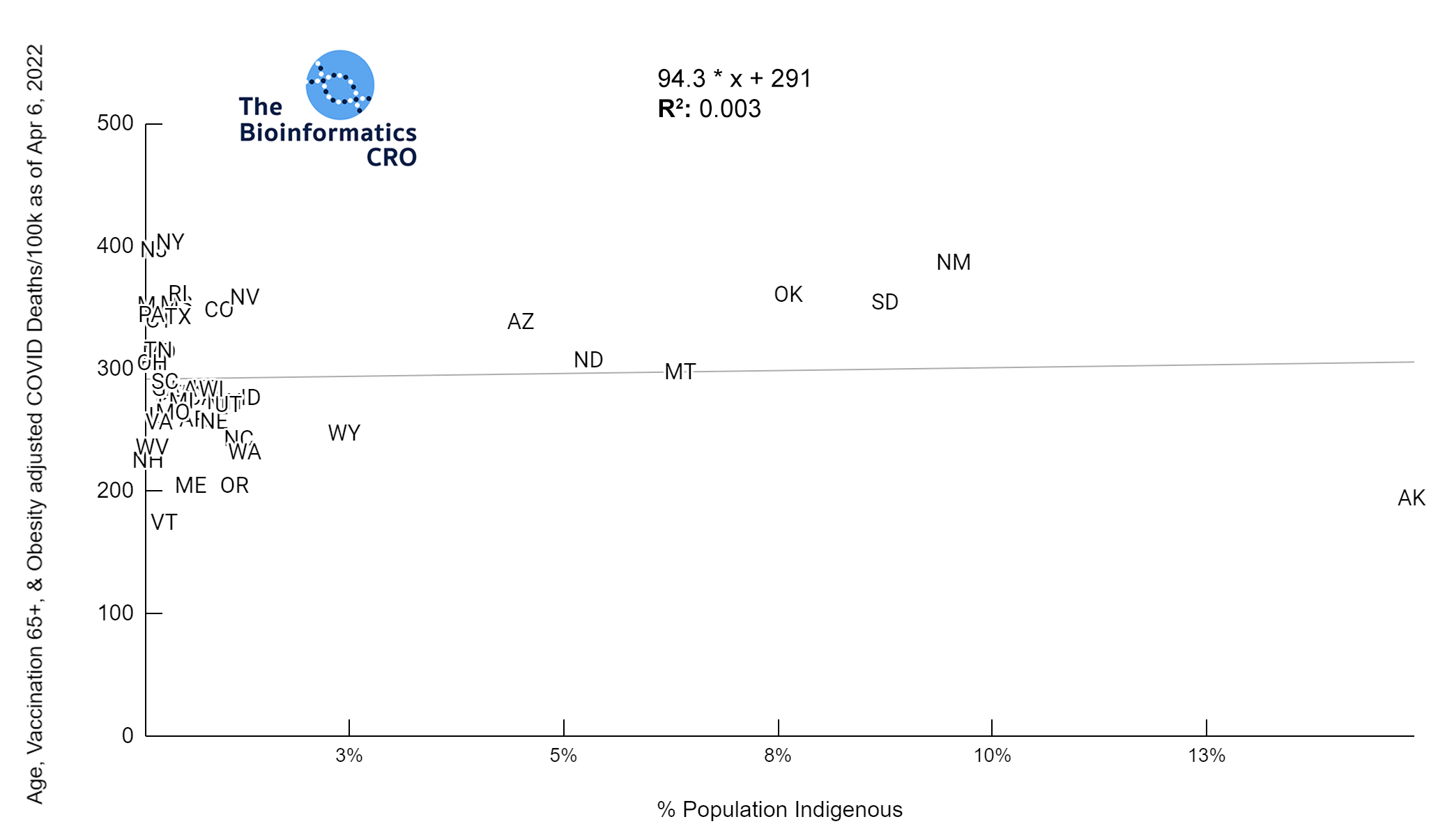

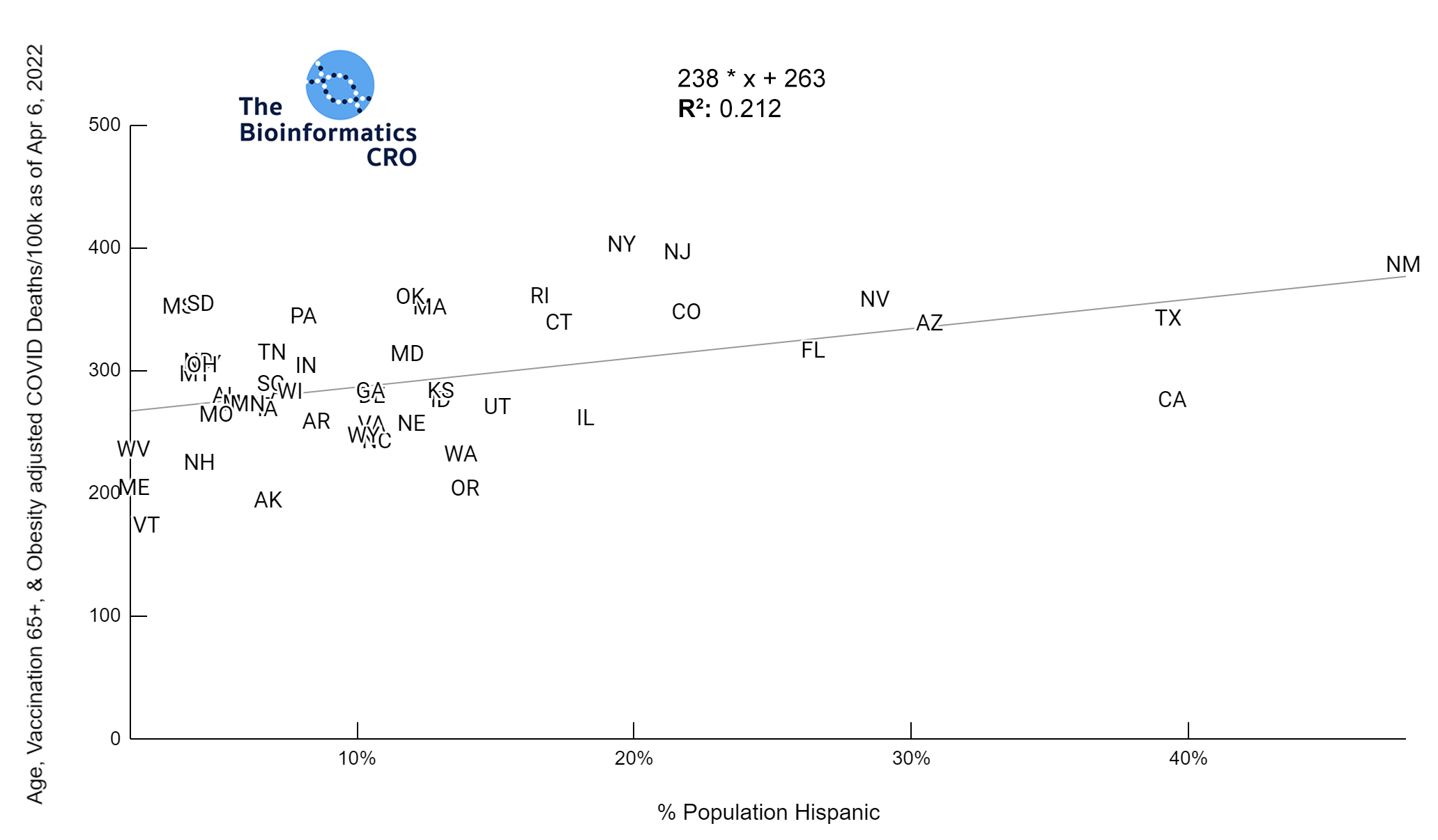

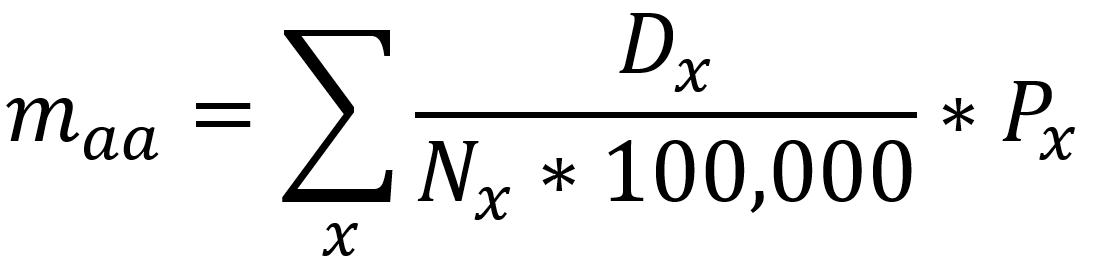

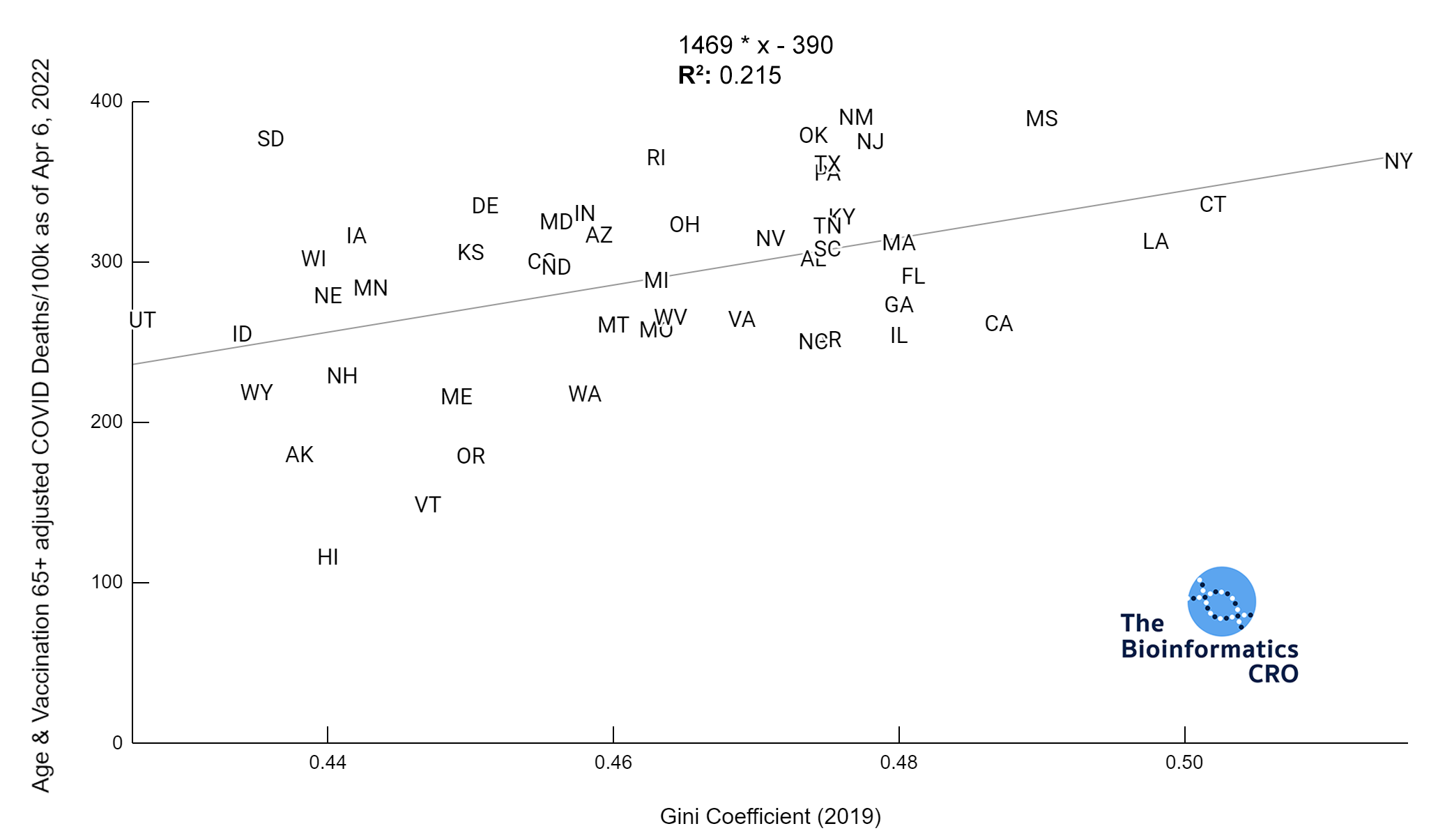

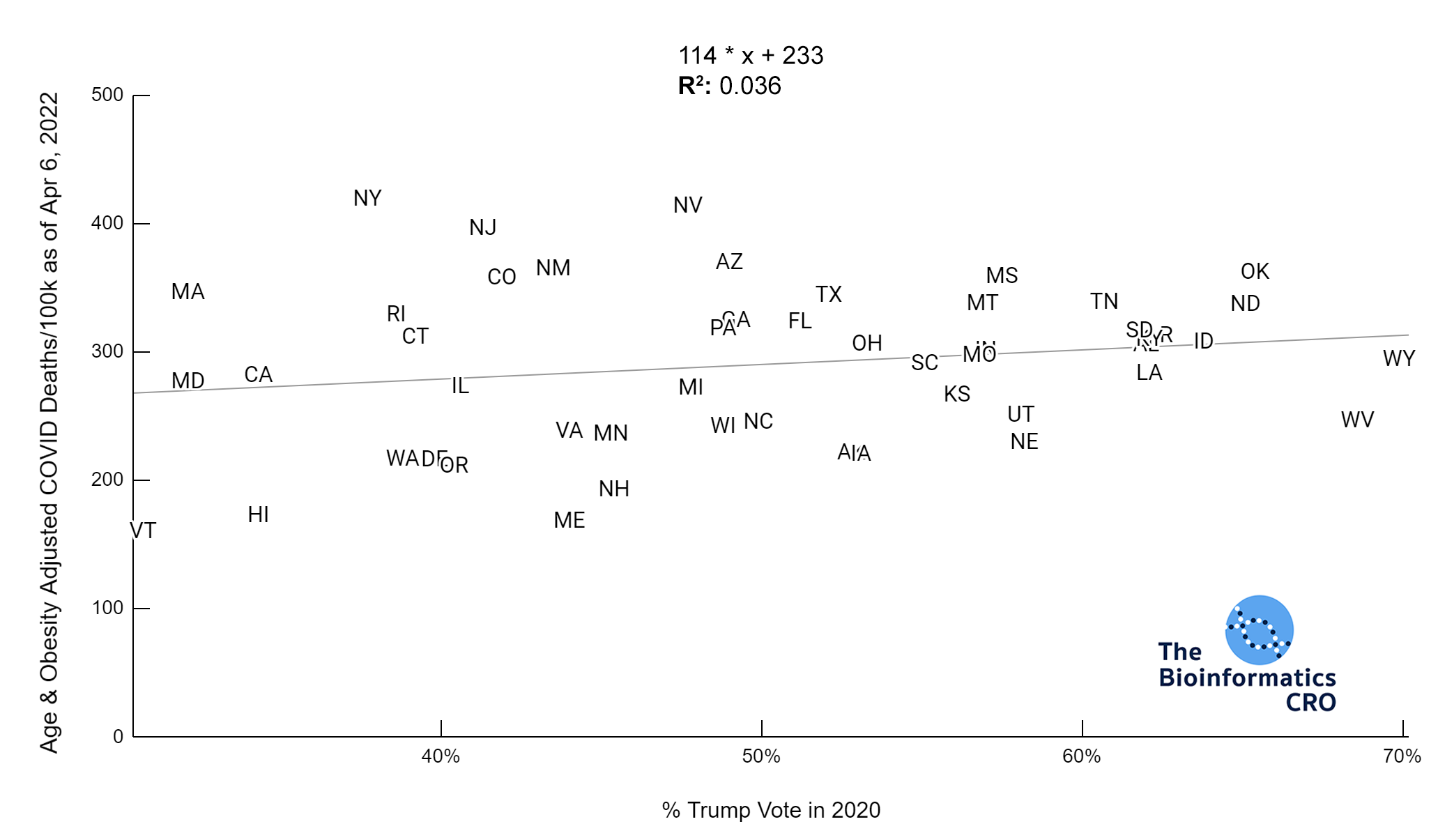

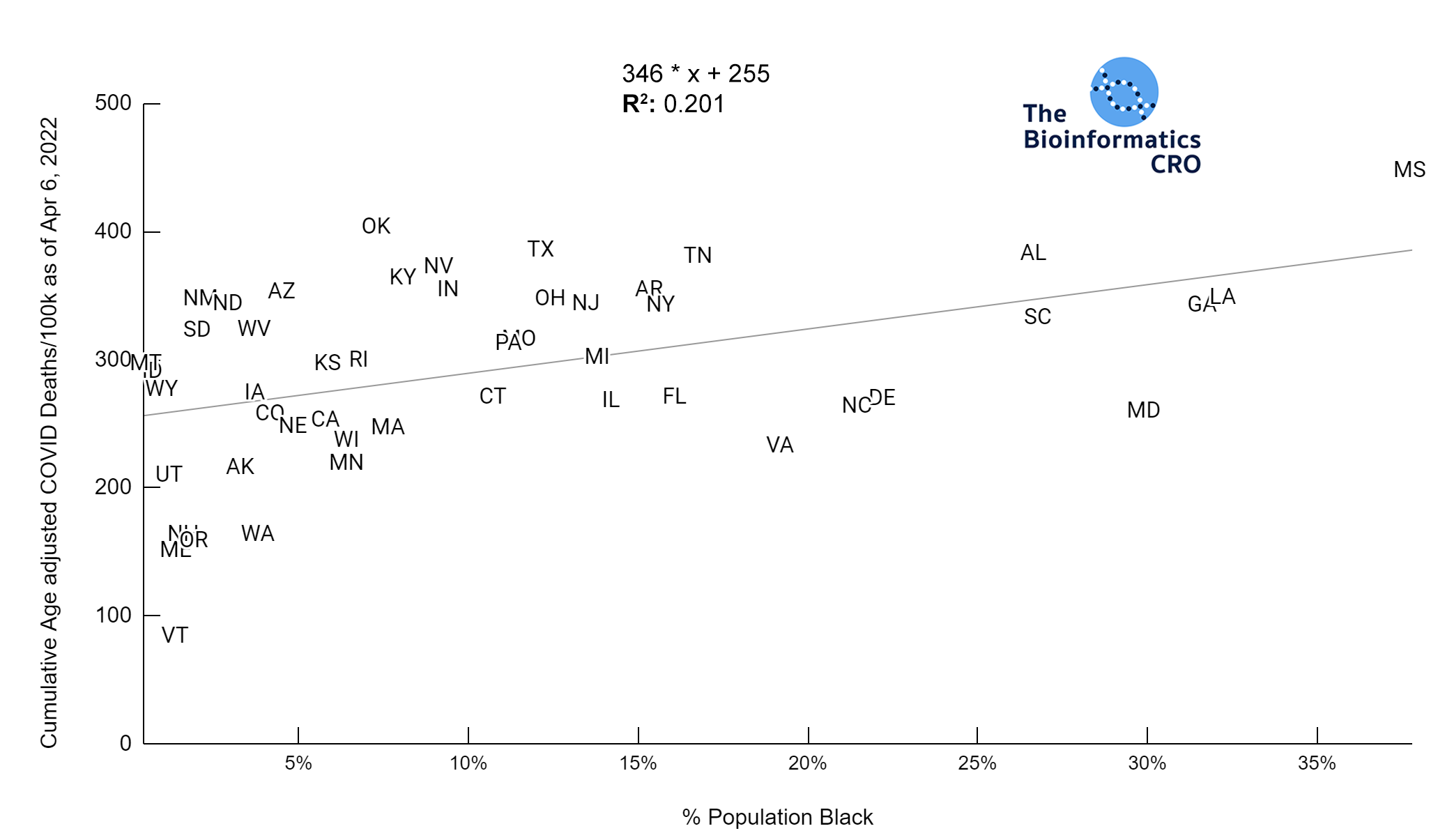

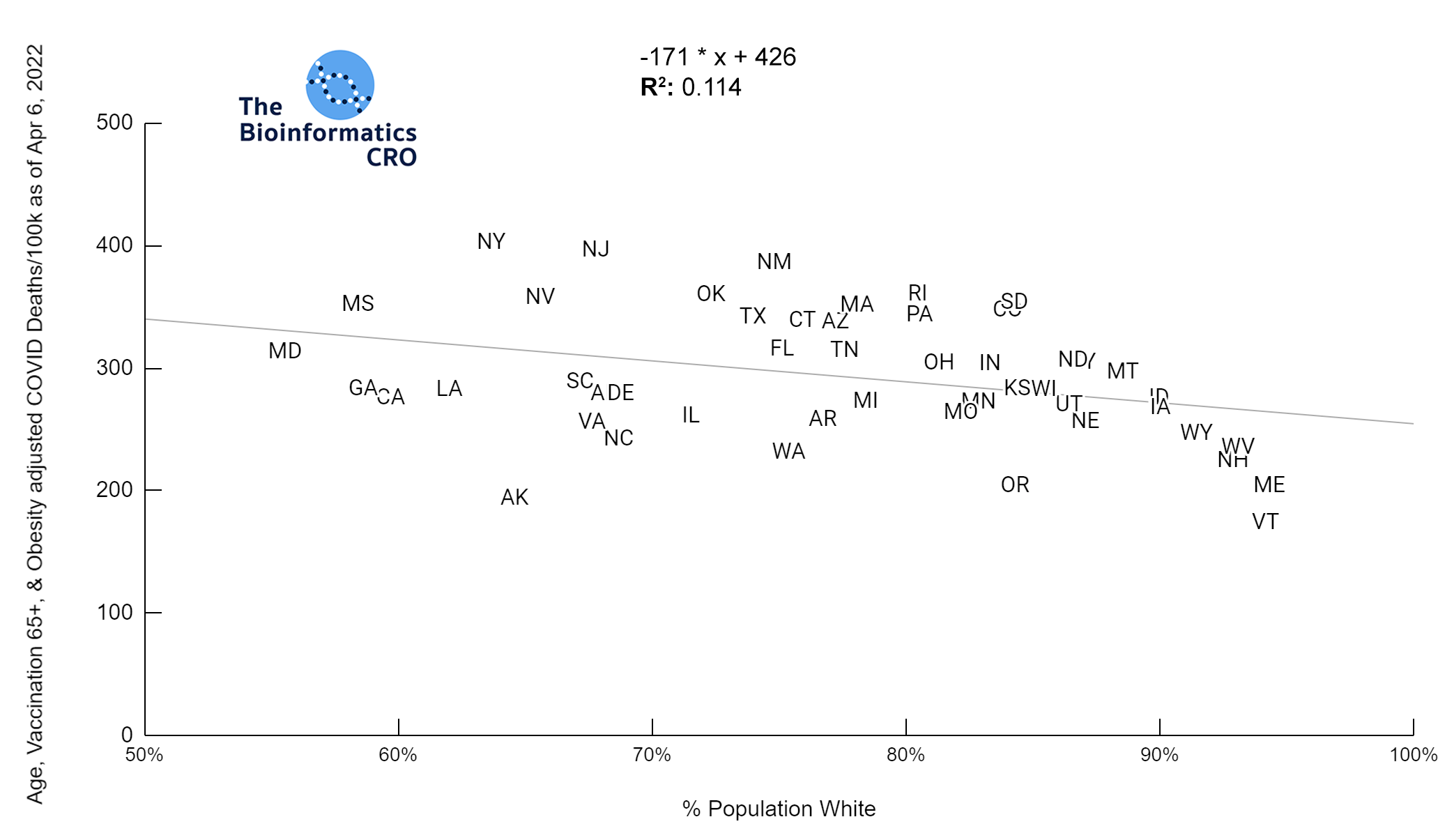

It should be noted that the race and ethnicity data are not normally distributed (Shapiro Test P<0.01 for all).

White P<0.05 | Black P=0.19 | Asian P=0.26 | Indigenous P=0.70 | Hispanic P<0.01

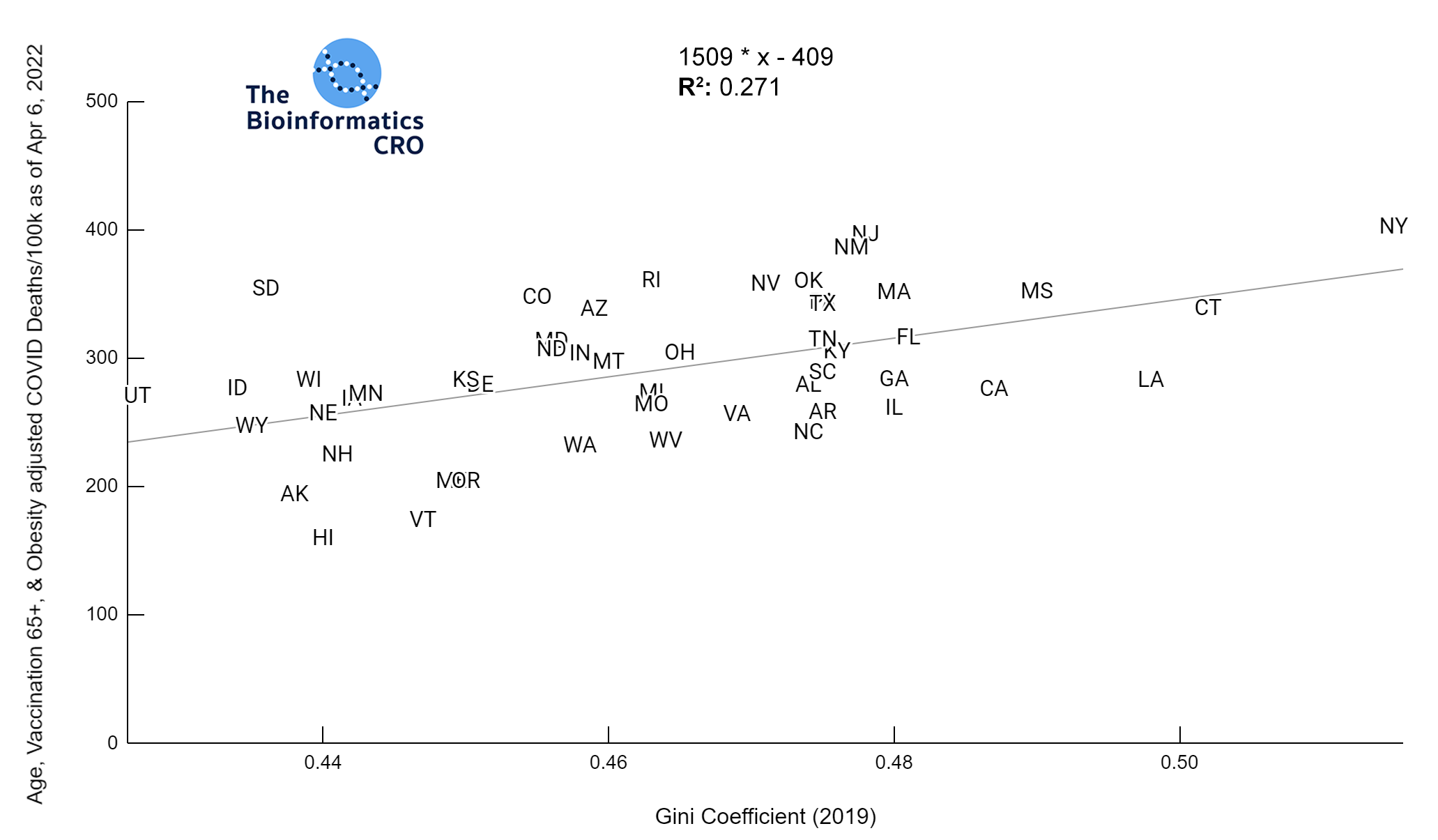

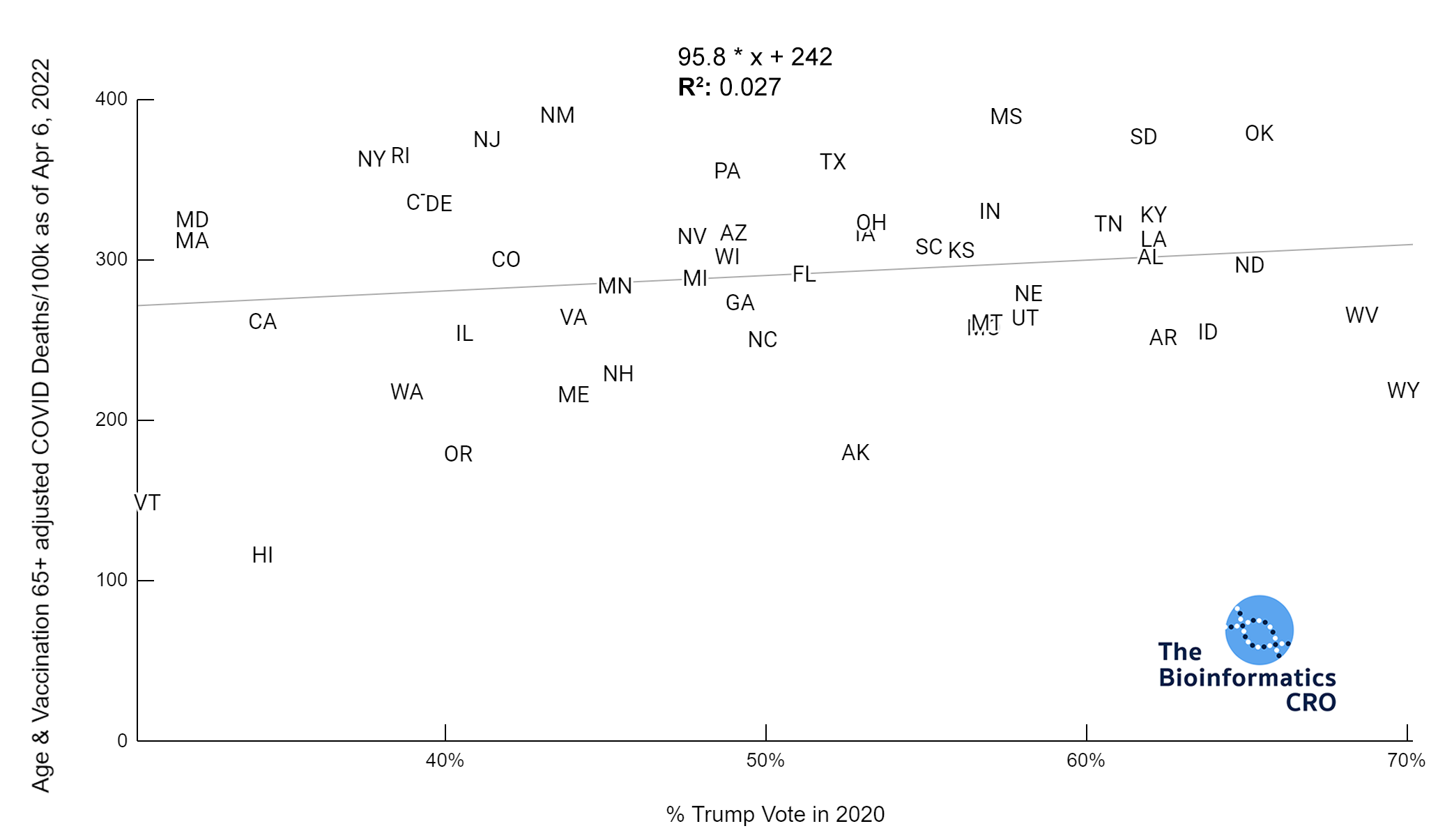

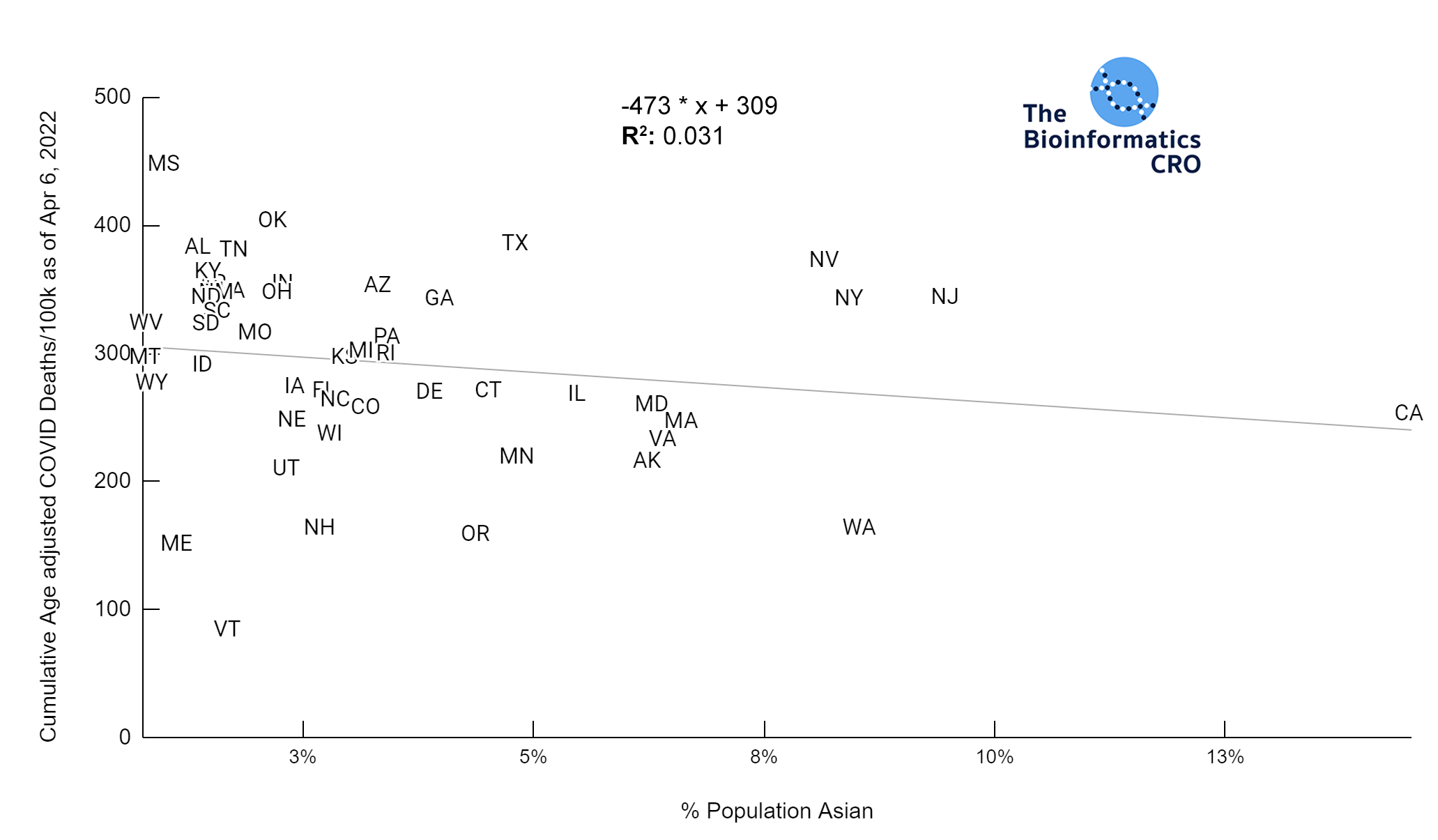

It should be noted that the race and ethnicity data are not normally distributed (Shapiro Test P<0.01 for all).

White P<0.05 | Black P=0.19 | Asian P=0.26 | Indigenous P=0.70 | Hispanic P<0.01